Atherosclerosis in Young Adults: What to Do After a Positive Coronary Calcium Scan

Introduction

Atherosclerosis is the primary health abnormality underlying several common causes of cardiovascular disease, including heart attack and stroke. While often regarded as a condition that affects older adults, medical imaging now allows for the early detection of atherosclerosis years or decades before symptoms or serious health outcomes occur. This includes coronary artery calcium (CAC) scoring, carotid ultrasound, and incidental findings on other imaging studies. While the detection of atherosclerosis at any age is an important finding, it can be an alarming test result for young adults, many of whom are seemingly healthy and uncertain what to do next. The purpose of this article is to outline a strategy for optimizing and identifying cardiovascular risk factors in young individuals with early stages of atherosclerosis. Meanwhile, this information is relevant to individuals of all ages.

For young individuals in their 30s and 40s, the identification of atherosclerosis or coronary artery calcification suggests the presence of strong genetic risk factors, cardiometabolic abnormalities, or other contributing exposures. Therefore, a more proactive approach to identify underlying risk factors of atherosclerosis is appropriate. If these risk factors are identified and addressed early, there is the potential to favorably influence the long-term trajectory of cardiovascular health for decades to come.

Priorities for Young Individuals With Atherosclerosis:

- Maximize cardiorespiratory fitness.

- Achieve desired ApoB/LDL-C targets.

- Identify and optimize additional cardiovascular risk factors

(e.g. metabolic, hormonal, inflammatory, genetic, etc.).

Both aerobic exercise and lipid lowering medications have been shown to stabilize atherosclerosis, and in some cases, the ability to reduce atherosclerotic plaque volume.1-8 In addition to maximizing cardiorespiratory fitness and achieving optimal ApoB/LDL-C goals, a comprehensive health evaluation is warranted to identify additional risk factors for premature vascular injury. This includes a thorough analysis of cardiorespiratory fitness, metabolic health, insulin resistance, blood pressure, sleep health, visceral adiposity, the possibility subclinical hypothyroidism, chronic inflammation, or autoimmune illness, lifestyle and environmental exposures, as well as genetic abnormalities affecting lipoprotein levels and other metabolic pathways such as homocysteine.

While a thorough evaluation can uncover modifiable risk factors, it’s important to recognize that cardiovascular risk is not fully captured by blood work alone. Some individuals may develop atherosclerosis in the absence of traditional risk factors, while others may experience disease progression out of proportion to their measured risk. This reflects the complex interplay of genetic susceptibility, metabolic individuality, and biological factors not yet fully understood or easily tested. Until further scientific advances occur, a detailed family history remains a highly valuable tool for assessing cardiovascular risk in young adults.

Additional reading:

(1) How To Reverse Atherosclerosis

(2) Overcoming the Risk of Elevated Lp(a)

(3) Insulin Resistance as a Risk Factor of Cardiovascular Disease

Related Podcast Episode

Disclaimer

This content is intended for general educational and informational purposes only and does not represent the practice of medicine, medical advice, diagnosis, or treatment. Furthermore, no patient relationship is established by accessing or interacting with this content. Individuals should consult their personal healthcare provider before making any changes to their diet, lifestyle, medications, or other aspects of their health. Additionally, I have no financial conflicts of interest or affiliations with any diagnostic testing or pharmaceutical companies mentioned in this article.

Notify Me of New Content

Provide your email address to receive notifications of new blog posts and podcast episodes.

Content Summary

Why Coronary Artery Calcium Matters in Younger Adults

Coronary artery calcium (CAC) is a powerful marker of atherosclerosis that offers direct insight into the amount and extent of atherosclerosis present. Unlike traditional risk calculators that often underestimate 10-year cardiovascular risk in younger individuals, CAC reflects the actual presence of atherosclerosis, not just statistical probability.21-23 Importantly, CAC scores are linearly associated with cardiovascular risk, independent of age, sex, or race.9 Even in adults under 45 years of age, a CAC score above zero is associated with a significantly higher long-term risk of cardiovascular events compared to individuals with a score of zero.24,25 As a result, the detection of coronary artery calcification in young individuals should prompt a thoughtful evaluation into the underlying drivers of vascular injury, as well as a proactive strategy to prevent progression.

Comprehensive Risk Assessment In Those With a Positive CAC

A positive coronary artery calcium (CAC) scan in a young adult should not be dismissed as incidental or routine. Rather, it represents premature vascular injury that warrants a thoughtful evaluation of possible explanations for an accelerated development of atherosclerosis. Why did this process begin so early? What underlying risk factors are present? Although many of these contributing factors are modifiable, they frequently go unrecognized in routine clinical practice.

The following section outlines a framework that I use to identify cardiovascular risk factors in young individuals. These risk factors are not listed in order of importance, and not every test is appropriate for every individual. Most importantly, interpretation should be guided by a qualified healthcare professional. Some test results, for example, those related to inflammatory and autoimmune illness, cannot be interpreted with blood work alone and must be assessed in the context of a detailed history and physical examination.

1. Body Composition, Cardiorespiratory Fitness, and Sleep

These domains form the foundation of cardiovascular and metabolic health. Objective measurements in these categories can serve as motivating information for personal improvement and individualized treatment priorities.

- Body Composition

While body mass index (BMI) is commonly used as a surrogate marker of body composition, whole-body DEXA scan offers a more detailed analysis of total body fat, fat distribution, and skeletal muscle mass. Intra-abdominal obesity (visceral adiposity), in particular, is a powerful predictor of cardiovascular risk, not captured with routine BMI estimations. If whole-body DEXA is not available or affordable, simpler tools such as waist-to-height ratio (WHtR) and waist-to-hip ratio (WHR) can offer relevant insight. - Cardiorespiratory Fitness

Cardiorespiratory fitness is one of the strongest predictors of both cardiovascular disease and all-cause mortality.26-28 It is commonly estimated using VO₂ max, which reflects the body’s maximal oxygen uptake during exercise. Tracking VO₂ max offers a quantifiable way to monitor personal fitness improvements over time and provides useful context by comparing results to age-based norms (Tables 2-3). Strategies to improve VO₂ max typically involve structured aerobic exercise, which has been shown to stabilize atherosclerosis, in some cases, to reduce plaque volume. - Blood Pressure

Elevated blood pressure accelerates atherosclerosis through several mechanisms, including blood vessel injury and increased penetration of atherogenic lipoproteins into the arterial wall.29,30 Although hypertension becomes more prevalent with age, it is necessary to screen for high blood pressure in young adults with evidence of coronary artery calcification. Blood pressure readings above 120/80 mmHg should prompt increased monitoring, lifestyle modification, and professional guidance regarding the appropriateness of prescription medication. 24-hour ambulatory blood pressure monitoring remains a highly informative yet underutilized tool for identifying high blood pressure in at-risk individuals. - Obstructive Sleep Apnea

Obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) is an important and underrecognized risk factor of cardiovascular disease. Young adults with coronary atherosclerosis, particularly those who are overweight or experience snoring or daytime fatigue, should be screened by a licensed healthcare professional. Common screening tools include a clinical history and scoring systems such as STOP-BANG. Confirmatory testing may lead to interventions like CPAP, which has been shown to improve blood pressure and possibly reduce the likelihood of cardiovascular events.31

2. Lipid and Lipoprotein Profile

While the standard lipid panel offers useful information for cardiovascular risk assessment, scientific advancements have led to more precise testing methods that better reflect the true risk of atherogenic lipoproteins.

- Apolipoprotein B (ApoB)

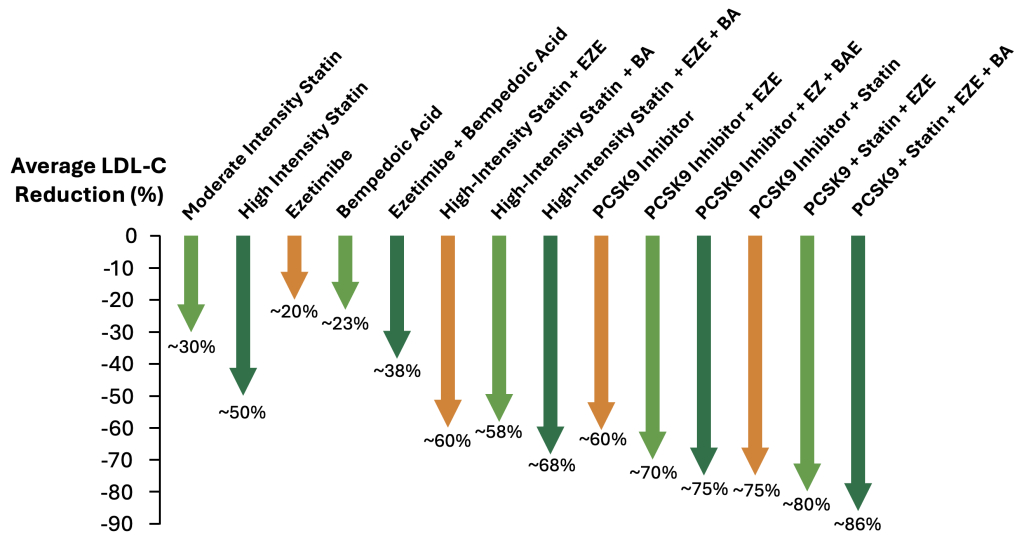

ApoB is a newer testing strategy that quantifies the total number of circulating atherogenic lipoprotein particles (LDL, Lp(a), VLDL, IDL) and it is recognized as a more accurate predictor of cardiovascular risk than LDL-C. For individuals with early signs of atherosclerosis (positive CAC), or those at high cardiovascular risk, current guidelines recommend targeting ApoB levels below 45 to 80 mg/dL depending on individual circumstances.15,16 Importantly, clinical trials have shown that greater reductions in ApoB and LDL-C beyond standard targets are associated with further reductions in cardiovascular events, supporting a more aggressive lipid-lowering approach in selected high-risk individuals.17-20 While lifestyle interventions such as increased dietary fiber and reduced saturated fat intake can meaningfully lower ApoB levels, many individuals will require prescription medications to reach these specified goals (See Figure 1 below, Average reduction of LDL-C with different lipid-lowering therapies). - Lipoprotein(a)

Lipoprotein(a), abbreviated as Lp(a), is a genetically determined lipoprotein that is strongly associated with cardiovascular disease. On a per-particle basis, it is estimated to be approximately 6.6 times more atherogenic than LDL.32 While there are currently no FDA-approved medications for the targeted lowering of Lp(a), PCSK9 inhibitors have been shown to reduce levels in many.33-35 Meanwhile, there is compelling evidence to suggest that a healthy diet, regular physical fitness, and healthy lifestyle choices can mitigate a significant amount of Lp(a)-associated cardiovascular risk. - Advanced Lipid Testing

LabCorp and Quest Diagnostics both offer advanced lipoprotein testing, which provides additional detail on lipoprotein size, density, and subclass distribution. While these measurements do not add independent predictive value once ApoB is known, they can still offer insight into related, modifiable risk factors. For example, a predominance of small, dense LDL particles, often referred to as LDL particle “Pattern B”, is strongly associated with insulin resistance and poor metabolic health, highlighting an additional opportunity for targeted lifestyle changes, treatment, and further testing. - Standard Lipid Panel

While ApoB is preferred over LDL-C for assessing atherogenic particle burden, traditional lipid panel values still provide important clinical insight. Low HDL-C, for instance, is not a direct cause of cardiovascular disease but serves as a strong marker of underlying metabolic dysfunction, particularly when accompanied by insulin resistance or elevated triglycerides. Fasting triglycerides should ideally be below 130 mg/dL, with optimal levels under 100 mg/dL. Elevated triglycerides, especially when paired with low HDL-C, are a sensitive indicator of insulin resistance and can help guide further optimization of metabolic and cardiovascular health.

3. Metabolic Health and Insulin Resistance

Insulin resistance and metabolic dysfunction are among the strongest risk factors of cardiovascular disease and can also affect individuals with a normal body weight (Table 1).

- Insulin Resistance

While optimizing ApoB/LDL-C levels remains the priority of cardiovascular risk reduction, there is evidence to suggest that insulin resistance is among the strongest risk factors of atherosclerosis (Table1). Unfortunately, standard glucose-based tests such as fasting glucose, hemoglobin A1c, and continuous glucose monitoring (CGM), often fail to detect insulin resistance in its early stages, as glucose levels can remain normal for years due to elevated levels of insulin (hyperinsulinemia). Instead, more sensitive tests capable of identifying early stages of insulin resistance include the Lipoprotein Insulin Resistance (LPIR) Score, Triglyceride-Glucose Index (TyG Index), and HOMA-IR. - Hemoglobin A1c

Hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c) reflects average blood glucose levels over the past 2–3 months. While it is valuable for monitoring more advanced states of abnormal glucose control, it is relatively insensitive to early stages of insulin resistance. This is due to the body’s ability to maintain normal glucose levels for years by releasing greater amounts of insulin. As a result, insulin resistance may be present before abnormalities are observed in HbA1c, fasting glucose, or continuous glucose monitoring. - Liver Health

Elevations in liver enzymes such as ALT and AST may indicate liver inflammation or injury, often related to excess intra-abdominal fat and the development of metabolic-associated steatotic liver disease (MASLD). When liver enzymes are persistently elevated, further evaluation with diagnostic imaging, such as ultrasound or elastography, may be warranted to assess for fat accumulation within the liver and potential scarring (fibrosis). - Uric Acid

Elevated levels of uric acid, even in the absence of gout, have been associated with an increased risk of atherosclerosis.36,37 Dietary and lifestyle modifications, including reduced intake of fructose and alcohol, can reduce uric acid levels and improve overall metabolic health.38,39 In cases of persistent elevation or recurrent gout, medications such as allopurinol or febuxostat may be appropriate. Additionally, colchicine has demonstrated cardiovascular benefit in certain populations, likely through its ability to reduce vascular inflammation and stabilize atherosclerotic plaque.40,41 - Homocysteine

Homocysteine is an amino acid produced during the metabolism of methionine. When elevated, homocysteine is associated with blood vessel dysfunction, oxidative stress, and increased risk of thrombosis, all of which may contribute to atherosclerosis. Homocysteine levels may become elevated due to nutritional deficiencies or genetic mutations affecting the MTHFR gene. Among individuals with elevated levels of homocysteine, further evaluation may be appropriate, as vitamin supplementation is often a simple solution to normalize homocysteine levels.

4. Chronic Inflammation and Immune Dysregulation

Persistent states of low-grade inflammation are known to accelerate the risk of blood vessel injury and development of atherosclerosis. In many individuals, elevated measurements of inflammation often reflect poor metabolic health. However, other causes of chronic inflammation can include autoimmune illness and chronic infection.

- Systemic Inflammatory Markers

High-sensitivity C-reactive protein (hs-CRP) is the most commonly used marker of systemic inflammation. Elevated hs-CRP levels are associated with increased cardiovascular risk, but the test itself is non-specific, meaning it cannot identify the underlying cause of inflammation. When elevated levels of hs-CRP are identified, this should prompt further evaluation by a licensed healthcare professional to identify and address the underlying source of inflammation. Additional markers of inflammation that may be tested include erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR), ferritin, and fibrinogen. - Autoimmune and Inflammatory Conditions

Autoimmune diseases such as rheumatoid arthritis, psoriasis, lupus, ankylosing spondylitis, Hashimoto’s thyroiditis, Crohn’s disease, ulcerative colitis, and celiac disease can contribute to chronic inflammation and accelerated risk of atherosclerosis. In young adults, particularly those with persistently elevated inflammatory markers and associated symptoms such as symmetrical joint pain, rashes, mouth sores, hair thinning, or unexplained gastrointestinal issues, further evaluation by a licensed healthcare professional is warranted. - Chronic Infection

Chronic infections can also contribute to persistent low-grade inflammation, which may accelerate the development of atherosclerosis and promote plaque instability. While many infections could be involved, the most common and relevant examples include periodontal disease (poor oral health) and HIV.

5. Endocrine and Hormonal Factors

Hormonal imbalances can influence lipid metabolism, vascular function, and weight regulation.

- Thyroid Function

Thyroid hormones play a critical role in regulating lipid metabolism, energy levels, and cardiovascular function. Subclinical hypothyroidism, a condition where thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH) is elevated but free T4 remains within the normal range, has been associated with increased LDL-C/ApoB levels and impaired lipoprotein clearance. Meanwhile, Hashimoto’s thyroiditis, the most common cause of hypothyroidism, is an autoimmune condition that may go undiagnosed for years. TSH and free T4 are standard screening tests, with Thyroid Peroxidase (TPO) and Thyroglobulin (TgAb) antibodies used to support the diagnosis of autoimmune thyroiditis. - Sex Hormones

Sex hormones such as testosterone and estradiol significantly influence body composition, insulin sensitivity, vascular health, and energy levels. Abnormal levels may contribute to increased visceral fat, insulin resistance, and reduced muscle mass, all of which impact cardiovascular risk. Although not routinely tested in asymptomatic individuals, hormone evaluation may be appropriate in the setting of unexplained fatigue, sexual dysfunction, menstrual irregularities, or atypical body composition. - Polycystic Ovary Syndrome

Polycystic Ovary Syndrome (PCOS) is a common endocrine disorder in women characterized by excess androgens, ovulatory dysfunction, and ovarian cysts on imaging. PCOS is strongly associated with insulin resistance, chronic low-grade inflammation, and increased risk of early-onset atherosclerosis. Diagnosis is made by a licensed healthcare professional based on clinical history, physical examination, and supported by laboratory testing such as testosterone and DHEA-S, SHBG, LH-FSH ratio, markers of metabolic health, and, when appropriate, pelvic ultrasound.

6. Lifestyle and Environmental Exposures

Harmful lifestyle and environmental exposures can contribute to vascular injury and risk of atherosclerosis. While the magnitude of risk varies by exposure and individual context, research continues to explore their relative impact. Importantly, some individuals may have genetic susceptibilities that amplify the vascular or immune consequences of these exposures, potentially accelerating the development of atherosclerosis.

- Alcohol Use

Alcohol consumption can contribute to elevated blood pressure, endothelial dysfunction, increased risk of cardiac arrhythmia, and in more severe cases, alcohol-induced cardiomyopathy. Although moderate alcohol intake has historically been viewed as “cardioprotective” due to its prevalence in Mediterranean populations and its association with higher levels of HDL cholesterol, emerging data suggest that even low to moderate alcohol intake may increase the risk of cardiovascular dysfunction and impaired metabolic health.42,43 Given these concerns, in young individuals with evidence of early atherosclerosis, minimizing or avoiding alcohol is a reasonable strategy to reduce potential harm. - Tobacco and Nicotine Products

Tobacco use is a well-established risk factor of atherosclerosis and plaque instability. Meanwhile, the use of nicotine-only products, such as e-cigarettes and pouches, have surged in popularity. At this time, there is limited evidence clarifying the long-term cardiovascular impact of these nicotine-only products, with some short-term studies demonstrating adverse effects on biomarkers of vascular health.44,45 While we await additional scientific research, it is also important to consider the possibility that certain individuals may have a genetic predisposition that heightens vulnerability to nicotine-related vascular injury.46,47 In young individuals with early atherosclerosis, minimizing or avoiding tobacco and nicotine use is a reasonable approach to reduce cardiovascular risk. - Trans Fats, Hydrogenated, and Partially Hydrogenated Oils

Industrially-manufactured trans fats and partially hydrogenated oils are known to contribute to vascular inflammation, adverse lipoprotein metabolism, and endothelial dysfunction.48 077853Although regulatory efforts have significantly reduced their consumption in many countries, these harmful ingredients can still be found in highly processed foods. For individuals with or without atherosclerosis, it is advisable to avoid foods containing industrial trans fats, hydrogenated oils, and partially hydrogenated oils. - Radiation and Other Environmental Exposures

While some environmental exposures are not easily modifiable, and their individual impact on cardiovascular risk may be modest or uncertain, emerging evidence has linked certain chemicals to vascular inflammation and injury. These include per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS, or “forever chemicals”), bisphenol A (BPA), and heavy metals. Although complete avoidance is not possible, practical strategies exist to reduce one’s exposure. Separately, previous exposure to radiation therapy to the head, neck, or chest, can contribute to accelerated vascular injury and atherosclerosis, highlighting the importance of optimizing known cardiovascular risk factors in those with a history of radiation therapy.

7. Family History and Genetic Disorders

Genetic susceptibility to atherosclerosis is one of the strongest contributors to early-onset atherosclerosis. In some individuals, common genetic variants known as polymorphisms result in subtle increases in cardiovascular risk through a variety of biological factors. These variations are common in the general population and may contribute to small or significant cumulative cardiovascular risk. In contrast, pathogenic mutations, which are less common but more harmful, can directly impair key enzymes or receptors involved in lipid processing (e.g. LDLR, APOB, PCSK9, etc.), leading to markedly elevated cholesterol levels or accelerated arterial damage. These mutations are often responsible for inherited conditions like familial hypercholesterolemia. Therefore, a careful and thoughtful review of one’s family history may allow for personalized diagnostic and preventive strategies, including consideration of genetic testing of the affected individual or their family, when appropriate.

- Family History of Cardiovascular Disease

Having a close family member (e.g. parent or sibling) affected by cardiovascular disease is a well-established risk factor of atherosclerosis. This includes events like heart attacks, strokes, stent placements, or sudden cardiac death. The risk is even more notable when these events occur at younger ages. In such cases, a more proactive assessment of cardiovascular risk is often warranted, even if routine lab tests appear normal. - Multiple Affected Relatives

When several family members are affected by cardiovascular disease, especially at young ages, the likelihood of an inherited disorder increases. This includes conditions such as familial hypercholesterolemia or elevated lipoprotein(a), which often go undiagnosed in routine clinical care. In such cases, more aggressive risk factor modification is warranted. - Genetic Mutations and Inherited Disorders

In individuals with markedly elevated lipoprotein levels or a strong family history of early cardiovascular disease, genetic testing may help to identify harmful mutations such as LDLR, APOB, or PCSK9. Identifying a pathogenic mutation can result in modified treatment decisions, as well as improved screening strategies for at-risk family members.

Table 1. Risk Factors of Early Onset Cardiovascular Disease in the Women’s Health Study

| Risk Factor, per standard deviation increment | Age of Onset < 55 Years Adjusted Hazard Ratio |

| Insulin Resistance, LPIR Score | 6.40 |

| Systolic Blood Pressure | 2.24 |

| Triglycerides | 2.14 |

| Apolipoprotein B (ApoB) | 1.89 |

| C-Reactive Protein (CRP) | 1.76 |

| Body Mass Index (BMI) | 1.47 |

| LDL Cholesterol | 1.38 |

| Hemoglobin A1c | 1.38 |

| Lipoprotein(a) | 1.22 |

Achieving Ideal ApoB and LDL-C Targets

Lowering atherogenic lipoproteins remains one of the most well-studied and effective strategies for reducing cardiovascular events in individuals with atherosclerosis. Generally speaking, lower is better and in many instances, prescription medications are necessary to achieve these goals.

Among individuals with atherosclerosis on cardiovascular imaging (positive CAC), but without previous heart attack, stroke, or peripheral arterial disease, the 2022 American College of Cardiology Expert Consensus advocates a target LDL-C of ≤100 mg/dL in those with CAC scores of 1 to 99 Agatston units (AU), and ≤ 75 mg/dL for those with CAC greater than 100 AU and/or other risk factors.15 The updated 2025 European Society of Cardiology guidelines adopt even more aggressive targets, recommending LDL-C ≤ 70 mg/dL for high-risk individuals and ≤ 55 mg/dL for very high-risk individuals.16 Notably, these guidelines specify lipoprotein goals in terms of LDL-C and not ApoB. These LDL-C goals translate into ApoB goals of approximately 45 to 80 mg/dL.

Importantly, clinical trials in high-risk individuals have shown that greater reductions in ApoB and LDL-C beyond standard targets are associated with further reductions in cardiovascular events, supporting a more aggressive approach in certain high-risk individuals.17-20

Lipid-Lowering Medications

While lifestyle interventions can meaningfully reduce lipoprotein levels (e.g. increased dietary fiber, reduced saturated fat intake), many individuals will require prescription medications to reach these specified goals. To reach these goals, statin therapy remains the most commonly utilized first-line of therapy. Meanwhile, there is an array of other safe and effective therapies available, including ezetimibe, bempedoic acid, and PCSK9 inhibitors (Figure 1). The selection of medication is influenced by effectiveness, side-effect profile, insurance coverage, and affordability. These medicines can be used in combination with one another or in isolation.

Other Medication Considerations

In addition to lipid-lowering therapies, other prescription medications may reduce cardiovascular risk in certain individuals and should be considered with guidance from a healthcare professional. These treatments are not appropriate for everyone and require a personalized approach. Low-dose aspirin may be used in certain people with a significantly elevated CAC score, particularly when overall cardiovascular risk is high and bleeding risk is low. Blood pressure medications such as ACE inhibitors, ARBs, or beta-blockers can provide added benefit in individuals with hypertension, diabetes, or a history of cardiovascular events. For those with type 2 diabetes or excess weight, medications like GLP-1 receptor agonists and SGLT2 inhibitors have been shown to lower cardiovascular risk while also supporting improvements in blood sugar, kidney function, and weight. Colchicine, an anti-inflammatory agent, has demonstrated cardiovascular benefit in some individuals with established heart disease and may be considered in specific situations as part of a broader risk-reduction strategy.

Figure 1. Average reduction in LDL-C levels with different lipid-lowering therapies.16

Maximize Cardiorespiratory Fitness and Aerobic Exercise

Aerobic exercise is one of the most powerful interventions for improving vascular health and reducing long-term cardiovascular risk. Clinical trials have shown that aerobic exercise can stabilize and promote modest regression of atherosclerotic plaque volume. For example, in patients with established coronary artery disease, high-intensity interval training performed at 85-95% of peak heart rate resulted in measurable reductions in coronary plaque volume within six months.1 A separate study comparing moderate continuous training with aerobic interval training found similar benefits, with both modalities resulting in regression of plaque volume and necrotic core size.2 These findings suggest that a variety of aerobic exercise strategies can stabilize atherosclerosis and reduce plaque volume, making this a highly relevant intervention for young adults with evidence of early atherosclerosis.

A useful way to quantify improvements in aerobic fitness is through VO₂ max, which is defined as the maximal rate of oxygen consumption during exercise. The measurement of VO₂ max serves as a surrogate marker of cardiorespiratory fitness, enables comparison to age and sex-based norms, and provides a clear metric for tracking individual progress over time (Tables 2-3).

Table 2. VO₂ Max Values for Men (ml/kg/min)49

| Age group | Poor | Below Average | Average | Excellent | Superior |

| 20-29 | 33 | 40 | 46 | 52 | 58 |

| 30-39 | 32 | 37 | 42 | 48 | 54 |

| 40-49 | 30 | 34 | 39 | 45 | 51 |

| 50-59 | 26 | 30 | 35 | 41 | 46 |

| 60-69 | 23 | 27 | 31 | 36 | 42 |

| 70-79 | 20 | 24 | 28 | 33 | 38 |

Note: Adapted from data from the FRIEND and Cooper Clinic Data sets, for which values are averaged between the two data sets.49 Poor, Below Average, Average, Excellent, and Superior, refer to the 10th, 25th, 50th, 75th, and 90th percentile by age, respectively.

Table 3. VO₂ Max Values for Women (ml/kg/min)49

| Age Group | Poor | Below Average | Average | Excellent | Superior |

| 20-29 | 27 | 32 | 38 | 44 | 49 |

| 30-39 | 24 | 29 | 33 | 39 | 43 |

| 40-49 | 23 | 26 | 31 | 36 | 41 |

| 50-59 | 21 | 24 | 27 | 31 | 35 |

| 60-69 | 19 | 21 | 24 | 28 | 31 |

| 70-79 | 18 | 20 | 23 | 25 | 28 |

Note: Adapted from data from the FRIEND and Cooper Clinic Data sets, for which values are averaged between the two data sets.49 Poor, Below Average, Average, Excellent, and Superior, refer to the 10th, 25th, 50th, 75th, and 90th percentile by age, respectively.